The Black Press nationalized the plights of African Americans, while simultaneously centralizing black thoughts and improving the conditions of African Americans.

Black History

Journalism being accessible to African Americans played a significant part in the evolution of them being looked at as second-rate citizens to first class citizens. The Freedom’s Journal, the first African American owned and operated newspaper, expressed this breakthrough with its first publication stating, “Too long have others spoken for us . . . We wish to plead our own cause.”

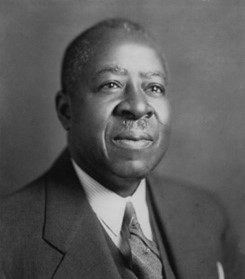

African American journalists led antislavery sentiment, depicted the violence, and the lack of justice involved in lynching, highlighted the importance of black leadership, and notified Southern African Americans of opportunities in Northern cities. One of the most notable black publications was the Chicago Defender, founded in 1905 by Robert S. Abbott. The Chicago Defender would be the first black-owned publication to have 100,000 publications in circulation and to include a health column and comic strips. The Chicago Defender produced the first black journalist millionaire. These are outstanding accomplishments, but you may wonder what social impact did that publication have?

The Defense

The Chicago Defender, initial issues included four paged, six-column handbills that Abbott sold door-to-door. However, as the magazine grew and hired new employees, the publication began to address racial injustices using yellow journalism and sensationalism to compete in the competitive market. The paper covered lynching, rapes, assaults of African Americans in the South and notified Southern African Americans of better opportunities in the Northern States. Though the publications covered topics on the black demographic in America, The Defender didn’t use the standard terminology of “Negro” or “black” to address his audience. Instead, he referred to them as the Race.

Before the black press, the media covered African Americans’ crimes and offered a white perspective on the atrocities devastating the black community, but the Chicago Defender provided grotesque descriptions and identified the core perpetrators as white mobs. Abbott’s Northern location allotted his unfiltered criticism of the occurrences in the South, but Southern states passed legislation banning black press from Southern states, under the guise that the publications were seditious. More than that, Ku Klux Klan members intimidated African Americans caught with the publications. Despite the opposition, most of the Defender’s audience were Southerners. Readers circulated the articles person to person and readers read them to their barbershops and congregations.

The Great Migration

The newspaper most notable impact on the black community was its campaign supporting the Great Migration movement. The Great Migration was the migration of half a million southern blacks to Midwestern/northern cities such as New York, Chicago, Detroit, and Pittsburgh during 1915-1925. The Defender publications included job opportunities and train schedules to encourage Southerners to leave their oppressed communities for better opportunities. Advertisements for beauty products, technological advancements, entertainment, and nightlife were included to allure Southern African Americans.

The Great Migration attributed to over 1.5 million African Americans relocate to Northern cities, and Chicago’s Black Belt, a predominantly black neighborhood surrounded by train tracks, increased 148%, pushing the total population to 109,458 (Hauad, 2012). After the Great Migration, The Chicago Defender published a weekly column of “dos” and “don’ts” to assimilate Southerners to the culture of the North. Some social faux pas the publication’s negative comments were chewing gum, talking loudly, wearing bright clothes, attending Nickelodeon theaters, listening to jazz music, and more.

A more significant number of migrations caused the South to lose a large portion of their workforce, and the persecution of the Chicago Defender continued. White southerners informed the federal government that the Defender was German propaganda to radicalize the black community, which resulted in the US Postal Service refusing to distribute the publication. Like all black media, the Defenders used black porters in luxury sleeper cars to distribute the newspapers in the South. The Pullman Porters throughout history; The Pullman Porters ensured black ideologies reached Southern blacks by stopping at center points, such as churches and barbershops, in black communities. The Great Migration helped benefit the Civil Rights Movement and was an artistic inspiration for the Harlem Renaissance.

National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA)

Robert Abbott appointed his nephew, John Sengstacke as his predecessor. Sengstacke organized a meeting of Black publishers from across the nation to convene in Chicago for “harmonizing our energies in a common purpose for the benefit of Negro journalism” (Wilson, 2016). Twenty-two publications’ representatives attended the meeting and decided to form the National News Paper Publishers Association (NNPA), formerly known as the National Negro Publishers Association. Since [the creation of the association], its inception has been at the forefront of black press and broadcasting opportunities for African Americans. The association currently comprises 205 black publications reaching over 20 million readers every day (NNPA, 2019).

References

Hauad, V. (2012, June 14). Robert S. Abbott and The Chicago Defender. Ohio State University. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://cpb-us-w2.wpmucdn.com/u.osu.edu/dist/1/3078/files/2012/06/Brad-Rowe.pdf

History.com Editors. (2010, March 4). The Great Migration. History.com. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/great-migration#section_4

National Newspaper Publishers Association (NNPA). NNPA. (2019, August 4). Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://nnpa.org/about-nnpa/

Teresa, C. (n.d.). The Jim Crow-era Black Press: Of and for its readership. The Jim Crow-era Black press: Of and for its readership | The American Historian. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://www.oah.org/tah/issues/2018/august/the-jim-crow-era-black-press-of-and-for-its-readership/

Wilson, C. C. (2016, July 18). Black Press history. NNPA. Retrieved February 18, 2022, from https://nnpa.org/black-press-history/