Public opinion does matter and your vote does, too. Years of struggle have gone into establishing freedom of expression for Americans, especially black people. Today, most African Americans are still struggling with their identity and a right to their native land in the United States of America. African Americans have set the pace for other minorities to find freedom in the American Melting Pot. Seasons have changed; growth has happened among the human race but still today there is an attitude of hostility that needs to be deflated so history doesn’t repeat itself. Let’s take a step back in time to Los Angeles, August 11, 1965.

The Incident

Minorities had many struggles during the early 1960s, by trying to establish justice and residency among society. In 1964, the Civil Rights Act was passed to balance race relations among society. This federal law was put to the challenge by states, for example, in the Proposition 14 clause that was created by California. Proposition 14 blocked the fair housing section of the Civil Rights Act. According to a PBS article on A Huey P. Newton Story-Times-Watts Riots, “This created anger and a feeling of injustice within the inner cities.”

African-Americans’ rights weren’t being accepted, but by law, there was potential for their rights to be established. President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into federal law on August 6, 1965. This bill was written into law for blacks to have the same rights as whites. This Act prohibited the states from using literacy tests that had infringed upon constitutional rights and other methods used to exclude African-Americans from voting. This bill created a significant change within the South, but new and unresolved issues were still at hand. Discrimination, high jobless rates, bad schools, poor housing, and the failure of the Rumford Fair Housing Act caused an outcry nationwide.

Rage in the Streets

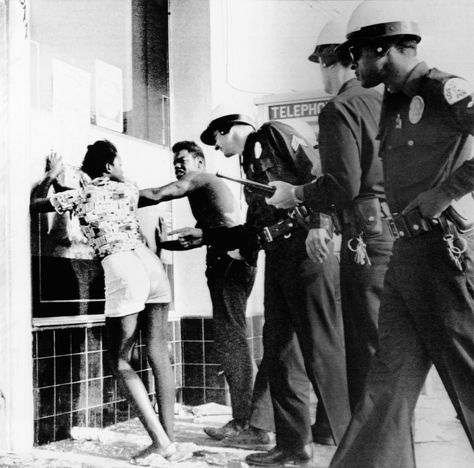

A violent rage settled through the city of Los Angeles, CA, because of speculation of police brutality. “On Wednesday August 11, 1965 rioting broke out in the Watts area of Los Angeles, CA, following the arrest of a suspected drunk driver by California Highway Patrol officers,” according to 1965 Watts Riots Police Radio Calls. This information had come across the LAPD’s radio frequencies that were “broadcasted and filed” during the times when dispatchers shared a single radio frequency.

Lee W. Minikus, a California Highway Patrolman, pulled over motorist Marquette Frye and his brother Ronald because of a said complaint by a passing motorist of reckless driving. Frye failed the sobriety test that led to a resistance of arrest and the onlooking crowd had grown in numbers. Mrs. Frye, the mother of the motorist, had come to pick up her son’s vehicle as more officers had arrived on the scene. Officers wouldn’t give her the car, and therefore she had become angrier which led to all three of the Fryes’ arrest. The officers had begun to hit the brothers with their nightsticks because they supposedly resisted arrest. The onlooking crowd had become larger and hostile due to the treatment of the Fryes. Within a few minutes there had grown “more than 1000 persons in the crowd,” according to the Los Angeles Commissioner’s Committee review of 144 hours in August 1965.

As the officers were leaving, it was said that someone in the crowd had spat on one of the officers. This incident had led to the arrest of a young black woman and a man. The officers were said to have become violent towards the crowd. The crowd had broken up into small groups and the incidents had become gossip spread throughout the predominately-black neighborhood of South Central Los Angeles. The outcome on that day had led to blacks pulling motorists from their cars and beating them, the stoning of any automobiles that passed and damage to a police post that was set up in their neighborhood.

On Thursday, the Los Angeles County Human Relations Commission had called a meeting. Many representatives from every neighborhood group had come to this meeting to discuss the problems growing within the inner cities. The media were also able to attend that meeting. The meeting took a bitter tone as some youths made remarks that aired nationwide via radio and television. Hal Humphrey of the Los Angeles Times stated later that broadcasting events like riots had tensed the hysteria of the citizens with “inflammatory commentary and unconfirmed reports”.

There were six horrible days of rioting going on around and in the Watts area. Warfare and bloodshed were the result. “More than 34 people died included in that total were a fireman, a Long Beach policeman and a deputy sheriff; 1000 wounded; and an estimated $50-$1000 million in property damage,” according to a PBS article on A Huey P. Newton Story-Times-Watts Riots. In the Commissioner’s reports, it was stated that Friday the 13th was the worst day of the Watts Riots.

While the firefighters moved in to put out buildings and car fires caused by residents of the community, the firefighters were shot at by snipers posted on other buildings or around corners. Police Chief William H. Parker had believed that at that point, more guards were needed. The riots had spread across the 46.5 square-mile district by Saturday because of the curfew that was put into effect because of looting and burning of buildings. The riot had spread to other areas of California: Pasadena, San Diego, Pacoima, Monrovia, Long Beach, San Pedro-Wilmington area, just to name a few. Lt. Governor Glen Anderson called the National Guards to come in because more than 3,000 people had gathered in the commercial section of Watts and had looted the business area.

That week 13,900 National Guardsmen and 934 Los Angeles Officers were the total used in the result of this horrific event. Gunfire waged between snipers, the Guardsmen, and the law enforcement officers went on throughout that night. The Commissioner’s Committee reports said that the spread of the riot was a result from broadcasting media news coverage. After the Watts Riots six-day destruction, Governor Brown had John McCone to lead a Commission and study the riots to prevent a reoccurrence, a plan to rebuild property that was destroyed and an effort to make better programs to improve the Watts community.

The Coverage

Newsweek was the first to refer to the south of Los Angeles area as the Watts in news media. Before the riots had developed, the magazine had done several articles on the need for development in the Watts area. Several media outlets assumed that this riot had nothing to do with race but problems that persist with the need for developing better opportunities for the neighborhood area. However, the Los Angeles Times also did stories concerning the South Central area of L.A. and was the first to get a detailed story on the Watts riots.

A civil rights correspondent, Karl Fleming of Newsweek, was seriously injured while trying to cover the riots. Helicopters were flown across the Watts area to broadcast the rioting on television news. The Los Angeles Times had tried to send reporters in but thought of a clever way to be able to go inside of the Watts area. The Times sent black Classified Advertising Salesman, Richard Richardson in to cover the rioting in the Watts area. He was the first African-American to report at the Times. Richardson was the first African-American to report at the Times, but in 1966 Ray Rodgers became the first black staff reporter of L. A. Times. Later, a movie called Heat Wave was made based on Richardson’s experiences during the Watts riot in 1990.

Richardson had driven to the scene and stayed in the phone booth. He leaned out every now and then to chant with the crowd the words “Burn, baby, burn.” He had to pretend that he was part of the riot because the rioters were beating every black middleclass man and white person on that location. He had called every chance he got to L. A. Times. Richardson reported that the police had stopped him and he had to yell “press.” He had witnessed two black males being beaten around a corner. A man who didn’t participate in the riot but stayed in the Watts area told Richardson that rioters were “only doing what others wouldn’t do,” but wanted to do. Richardson’s story made Times headlines as “Eye Witness Account” in order to let readers know that this was firsthand and detailed reporting.

News reporters and officials were trying to find blame and reason for the Watts riot. The Los Angeles Times was very efficient in covering the riot. The L. A. Times reporter, Hal Humphrey, stated that the coverage of the riot was too much. His headline of his article was “TV Riot Coverage Too Subjective.” He believed that the media had “heightened the hysteria”. The Times criticized broadcasting coverage for appearing to take sides. Humphrey believed that broadcasting had an “obligation of power” because people trusted what was being seen. Nothing could have been taken away or edited if it was live coverage.

New York Times ran a headline of “Officials Divided in Placing Blame.” The attitudes of officials towards each other didn’t make the situation any better. Los Angeles Police Chief William H. Parker was upset in the delay of National Guards being called by Lt. Governor Anderson. At the time, Governor Pat Brown was on vacation so Lt. Governor Anderson had filled in as acting governor for him. The New York Times stated how African-American leaders, civil rights leaders, and others were trying to express their opinions on how the government officials and law enforcement had handled the riots.

In conclusion, everyone had tried to place blame on how and why the Watts riot occurred. The best quote found on why the riots and looting took place was from a New York Times article “Officials Divided in Placing Blame.” Richard Gold, a white businessman said, “They are gripped by some sort of insanity. What’s behind this is pent up anger over poverty and miserable housing.” Race was not the main factor, but that issue did lay in-between police brutality and the treatment of the poor. In the commissioner’s report, the study showed that other disadvantaged groups faced the same problem, failed programs. “It’s an American problem” and it still is today. Let’s all aim to heal America.